Scenes

Letters from Amida Shrine

阿弥陀堂だより

Letters from Amida Shrine

Letters from Amida Shrine

English title: Letter from the mountains

Original title: 阿弥陀堂だより Amidadō dayori

Published: 2002

Length: 128 minutes

Staff

Director: Takashi Koizumi

Script: Takashi Koizumi, Keishi Nagi

Music: Takashi Kako

Cast

Akira Terao: Takao Ueda

Kanako Higuchi: Michiko Ueda

Shoji Arano

Hisashi Igawa: Sayuri's father

Kyoko Kagawa: Yone Koda

Tanie Kitabayashi: Oume

Manami Konishi: Sayuri Ishino

Yasuhiko Naito: mayor of the village

Yoko Shioya: Tanabe

Takahiro Tamura: Shigenaga Koda

Hidetaka Yoshioka: Dr. Nakamura

Japan, early 2000s. The writer Takao and his wife, the doctor Michiko, move from Tokyo to the village of Yanaka. Takao's parents' house is there. Michiko has burned out and Takao has been taking a creative break for 10 years.

Many old people live in the village. The dominant themes are health, illness, life and death.

Country life appears ideal in its simplicity and traditional way of life. 96-year-old Oume lives near the Amida Buddha memorial shrine for the dead of the village (Amidado). She dictates her thoughts to the mute young Sayuri. These are then published as "Letter from the Amida Shrine" in the village's news paper.

Old Koda Sensei, Takao's cancer-stricken former teacher, ponders life and death. He practices Shōdō (calligraphy) all the time. His motto is 天上大風 (てんじょう おおかぜ), "Up to the sky with a strong wind". He concludes that everything is form.

Takao and Michiko take relaxing walks in nature. Michiko recovers and gets well again. She can work part-time in the village hospital and also helps Sayuri with her serious illness.

A very slow film with nice pictures in the ambience of traditional Japan.

The film is based on the novel "Amidado dayori" from 1995 by Keishi Nagi (南木 佳士), a Japanese writer and doctor, his real name is Tetsuo Shimoda (* 1951). He has received several literary prizes since 1981, most recently in 2008 and 2009. From his own experience with depression and in the hospital, there are many works on the subject of life and death. The plot of the film is partly autobiographical.

The film quotes:

Miyazawa Kenji (1896-1933) was a Japanese poet and an author of children's books. Miyazawa was inspired by Mahayana Buddhism, especially the Lotus Sutra and the patriotic interpretations of Nichiren Buddhism (Kokuchūkai), which he saw as a guideline for his personal life.

Ryōkan Taigu (良寛 大愚) (1758–1831), a Zen monk and hermit. Some of his contemporaries saw in him a saint, some a great poet, some even just a peculiar and somewhat crazy Zen monk. His author's name Taigu (大愚) means "great fool". He loved the simple life in nature, surrounded by plants and animals, and did not even like to harm a louse. A special love for moonlight and pine trees is expressed in his poems. It was atypical for a monk that he liked to take part in village festivals of the farmers and also drank sake. He is also said to have enjoyed playing with children, which may be a reason for the children's scenes in the film.

Alexander Sergejewitsch Pushkin (Александр Серге́евич Пу́шкин) (1799-1837), the Russian national poet. Until Napoleon's invasion of Moscow in 1812, the Russian upper class spoke French. That began to change after the big fire in Moscow. In his works, Pushkin paved the way for the use of colloquial Russian. His narrative style is inextricably linked with Russian literature and has shaped numerous Russian poets.

A poem by Miyazawa Kenji. It was found after the poet's death. Its theme refers to the Buddhist Lotus Sutra.

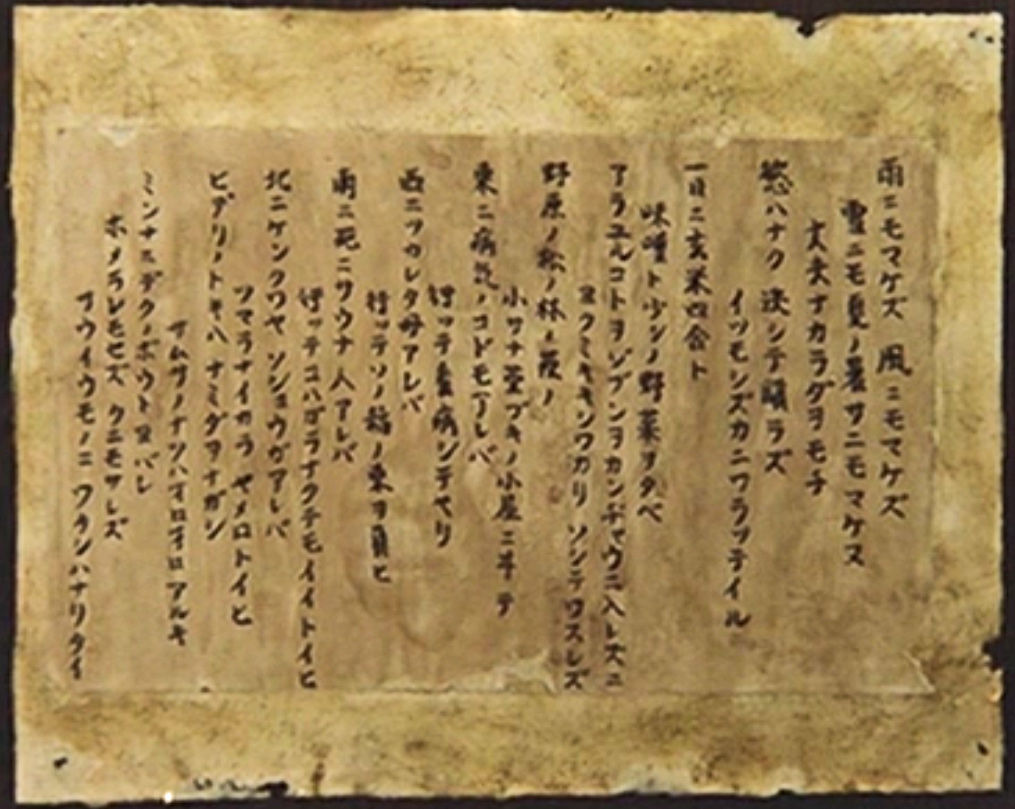

雨ニモマケズ 風ニモマケズ 雪ニモ夏ノ暑サニモマケヌ 丈夫ナカラダヲモチ 慾ハナク 決シテ瞋ラズ イツモシヅカニワラッテヰル 一日ニ玄米四合ト 味噌ト少シノ野菜ヲタベ アラユルコトヲ ジブンヲカンジョウニ入レズニ ヨクミキキシワカリ ソシテワスレズ 野原ノ松ノ林ノ蔭ノ 小サナ萓ブキノ小屋ニヰテ 東ニ病気ノコドモアレバ 行ッテ看病シテヤリ 西ニツカレタ母アレバ 行ッテソノ稲ノ朿ヲ負ヒ 南ニ死ニサウナ人アレバ 行ッテコハガラナクテモイヽトイヒ 北ニケンクヮヤソショウガアレバ ツマラナイカラヤメロトイヒ ヒドリノトキハナミダヲナガシ サムサノナツハオロオロアルキ ミンナニデクノボートヨバレ ホメラレモセズ クニモサレズ サウイフモノニ ワタシハナリタイ

"Not losing to the rain, not losing to the wind, not losing to the snow nor to summer's heat

with a strong body, not fettered by desire, by no means offending anyone, always quietly smiling

every day four gos of brown rice, miso and some vegetables to eat,

in everything do not put yourself in the equation, watching and listening, and understanding, and never forgetting

in the shade of the woods of the pines of the fields, being in a little thatched hut

if there is a sick child to the east, going and nursing over them

if there is a tired mother to the west, going and shouldering her sheaf of rice

if there is someone near death to the south, going and saying don’t be afraid

if there is a quarrel or a lawsuit to the north, telling them to not be so boring

when there's drought, shedding tears of sympathy

when the summer's cold, wandering upset

called a nobody by everyone, without being praised, without being a burden

such a person

I want to become."

Cold summers in Japan mean poor rice harvests, hence the phrase "when the summer's cold, wandering upset".

Miyazawa wrote the poem in katakana. Nowadays, Hiragana is used as a syllabary. The sparing use of Kanji was thought to make the poem more accessible to the rural population of Northern Japan with whom the poet lived.